Former-commit-id: 72a6194db8e0586e9b4b05f16898fff1516a07a3 [formerly 4353ca90022670878d3ccaef6d6ec886d110df0e] Former-commit-id: 3bbf849e7f2cf1c846f58f7a1d916fa1276279fc |

||

|---|---|---|

| .. | ||

| contracts | ||

| collation_test.go | ||

| collation.go | ||

| collator_client_test.go | ||

| collator_client.go | ||

| collator_test.go | ||

| collator.go | ||

| config_test.go | ||

| config.go | ||

| README.md | ||

| vmc.go | ||

Prysmatic Labs Main Sharding Reference

This document serves as a main reference for Prysmatic Labs' sharding implementation for the go-ethereum client, along with our roadmap and compilation of active research and approaches to various sharding schemes.

Table of Contents

- Sharding Introduction

- Roadmap Phases

- Go-Ethereum Sharding Alpha Implementation

- Security Considerations

- Beyond Phase 1

- Active Questions and Research

- Community Updates and Contributions

- Acknowledgements

- References

Sharding Introduction

Currently, every single node running the Ethereum network has to process every single transaction that goes through the network. This gives the blockchain a high amount of security because of how much validation goes into each block, but at the same time it means that an entire blockchain is only as fast as its individual nodes and not the sum of their parts. Currently, transactions on the EVM are not parallelizable, and every transaction is executed in sequence globally. The scalability problem then has to do with the idea that a blockchain can have at most 2 of these 3 properties: decentralization, security, and scalability.

If we have scalability and security, it would mean that our blockchain is centralized and that would allow it to have a faster throughput. Right now, Ethereum is decentralized and secure, but not scalable.

An approach to solving the scalability trilemma is the idea of blockchain sharding, where we split the entire state of the network into partitions called shards that contain their own independent piece of state and transaction history. In this system, certain nodes would process transactions only for certain shards, allowing the throughput of transactions processed in total across all shards to be much higher than having a single shard do all the work as the main chain does now.

Basic Sharding Idea and Design

A sharded blockchain system is made possible by having nodes store “signed metadata” in the main chain of latest changes within each shard chain. Through this, we manage to create a layer of abstraction that tells us enough information about the global, synced state of parallel shard chains. These messages are called collation headers, which are specific structures that encompass important information about the chainstate of a shard in question. Collations are created by actors known as proposer nodes or collators that are randomly tasked into packaging transactions and “selling” them to validator nodes that are then tasked into adding these collations into particular shards through a proof of stake system in a designated period of time.

These collations are holistic descriptions of the state and transactions on a certain shard. A collation header contains the following information:

- Information about what shard the collation corresponds to (let’s say shard 10)

- Information about the current state of the shard before all transactions are applied

- Information about what the state of the shard will be after all transactions are applied

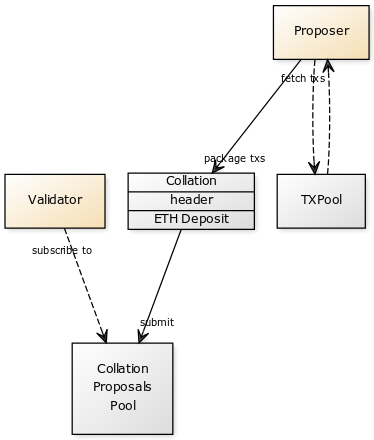

For detailed information on protocol primitives including collations, see: Protocol Primitives. We will have two types of nodes that do the heavy lifting of our sharding logic: proposers and validators. The basic role of proposers is to fetch pending transactions from the txpool, execute any state logic or computation, wrap them into collations, and submit them along with an ETH deposit to a proposals pool.

Validators then subscribe to updates in this proposals pool and accept collations that offer the highest payouts. Once validators are selected to add collations to a shard chain by adding their headers to a smart contract, and do so successfully, they get paid by the deposit the proposer offered.

To recap, the role of a validator is reach consensus through Proof of Stake on collations they receive in the period they are assigned to. This consensus will involve validation and data availability proofs of collations proposed to them by proposer nodes, along with validating collations from the immediate past (See: Windback).

When processing collations, proposer nodes download the merkle branches of the state that transactions within their collations need. In the case of cross-shard transactions, an access list of the state along with transaction receipts are required as part of the transaction primitive (See: Protocol Primitives). Additionally, these proposers need to provide proofs of availability and validity when submitting collations for “sale” to validators. This submission process is akin to the current transaction fee open bidding market where miners accept the transactions that offer the most competitive (highest) transaction fees first. This abstract separation of concerns between validators and proposers allows for more computational efficiency within the system, as validators will not have to do the heavy lifting of state execution and focus solely on consensus through fork-choice rules.

When deciding and signing a proposed, valid collation, collators have the responsibility of finding the longest valid shard chain within the longest valid main chain.

In this new protocol, a block is valid when

- Transactions in all collations are valid

- The state of collations after the transactions is the same as what the collation headers specified

Given that we are splitting up the global state of the Ethereum blockchain into shards, new types of attacks arise because fewer hash power is required to completely dominate a shard. This is why the source of randomness that assigns validators and the fixed period period of time each validator has on a particular shard is critical to ensuring the integrity of the system.

The Ethereum Wiki’s Sharding FAQ suggests random sampling of validators on each shard. The goal is so these validators will not know which shard they will get in advance. Every shard will get assigned a bunch of collators and the ones that will actually be validating transactions will be randomly sampled from that set. Otherwise, malicious actors could concentrate hash power into a single shard and try to overtake it (See: 1% Attack).

Casper Proof of Stake (Casper FFG and CBC) makes this quite trivial because there is already a set of global validators that we can select validator nodes from. The source of randomness needs to be common to ensure that this sampling is entirely compulsory and can’t be gamed by the validators in question.

In practice, the first phase of sharding will not be a complete overhaul of the network, but rather an implementation through a smart contract on the main chain known as the Validator Manager Contract. Its responsibility is to manage shards and the sampling of proposed validators from a global validator set and will take responsibility for the global reconciliation of all shard states.

Among its basic responsibilities, the VMC will be responsible for reconciling validators across all shards, and will be in charge of pseudorandomly samping validators from a validator set of people that have staked ETH into the contract. The VMC will also be responsible for providing immediate collation header verification that records a valid collation header hash on-chain. In essence, sharding revolves around being able to store proofs of shard states on-chain through this smart contract.

The idea is that validators will be assigned to propose collations for only a certain timeframe, known as a period which we will define as a fixed number of blocks on the main chain. In each period, there can only be at most one valid collation per shard.

Roadmap Phases

Prysmatic Labs’ implementation will follow parts of the roadmap outlined by Vitalik in his Sharding FAQ to roll out a working version of quadratic sharding, with a few modifications on our releases.

- Phase 1: Basic VMC shard system with no cross-shard communication along with a proposer + validator node architecture

- Phase 2: Receipt-based, cross-shard communication

- Phase 3: Require collation headers to be added in as uncles instead of as transactions

- Phase 4: Tightly-coupled sharding with data availability proofs and robust security

To concretize these phases, we will be releasing our implementation of sharding for the geth client as follows:

The Ruby Release: Local Network

Our current work is focused on creating a localized version of phase 1, quadratic sharding that would include the following:

- A minimal, validator client system that will deploy a Validator Manager Contract to a locally running geth node

- Ability to deposit ETH into the validator manager contract through the command line and to be selected as a validator by the local VMC in addition to the ability to withdraw the ETH staked

- A proposer node client and Cryptoeconomic incentive system for proposer nodes to listen for pending tx’s, create collations, and submit them along with a deposit to validator nodes in the network

- A simple command line util to simulate pending transactions of different types posted to the local geth node’s txpool for the local collation proposer to begin proposing collation headers

- Ability to inspect the shard states and visualize the working system locally through the command line

We will forego many of the security considerations that will be critical for testnet and mainnet release for the purposes of demonstration and local network execution as part of the Ruby Release (See: Security Considerations Not Included in Ruby).

ETA: To be determined

The Sapphire Release: Ropsten Testnet

Part 1 of the Sapphire Release will focus around getting the Ruby Release polished enough to be live on an Ethereum testnet and manage a set of validators effectively processing collations through the on-chain VMC. This will require a lot more elaborate simulations around the safety of the pseudorandomness behind the validator assignments in the VMC and stress testing against DDoS attacks. Additionally, it will be the first release to have real users proposing collations concurrently along with validators that can accept these proposals and add their headers to the VMC.

Part 2 of the Sapphire Release will focus on implementing a cross-shard transaction mechanism via two-way pegging and the receipts system (as outlined in Beyond Phase 1) and getting that functionality ready to run on a local, private network as an extension to the Ruby Release.

ETA: To be determined

The Diamond Release: Ethereum Mainnet

The Diamond Release will reconcile the best parts of the previous releases and deploy a full-featured, cross-shard transaction system through a Validator Manager Contract on the Ethereum mainnet. As expected, this is the most difficult and time consuming release on the horizon for Prysmatic Labs. We plan on growing our community effort significantly over the first few releases to get all hands-on deck preparing for real ether to be staked in the VMC.

The Diamond Release should be considered the production release candidate for sharding Ethereum on the mainnet.

ETA: To Be

Go-Ethereum Sharding Alpha Implementation

Prysmatic Labs will begin by focusing its implementation entirely on the Ruby Release from our roadmap. We plan on being as pragmatic as possible to create something that can be locally run by any developer as soon as possible. Our initial deliverable will center around a command line tool that will serve as an entrypoint into a validator sharding client that allows for staking, a proposer client that allows for simple state execution and collation proposals, and processing of transactions into shards through on-chain verification via the Validator Manager Smart Contract.

Here is a full reference spec explaining how our initial system will function:

System Architecture

Our implementation revolves around 5 core components:

- A locally-running geth node that spins up an instance of the Ethereum blockchain

- A validator manager contract (VMC) that is deployed onto this blockchain instance

- A validator client that connects to the running geth node through JSON-RPC, provides bindings to the VMC, and listens for incoming collation proposals

- A proposer client that is tasked with state execution, processing pending tx’s from the Geth node, and creates collations that are then broadcast to validators via a wire protocol

- A user that will interact with the sharding client to become a validator and automatically process transactions into shards through the sharding client’s VMC bindings.

Our initial implementation will function through simple command line arguments that will allow a user running the local geth node to deposit ETH into the VMC and join as a validator that is automatically assigned to a certain period. We will also launch a proposer client that will create collations from the geth node’s tx pool and submit them to validators for them to add their headers to the VMC.

A basic, end-to-end example of the system is as follows:

-

A User Starts a Validator Client and Deposits 100ETH into the VMC: the sharding client connects to a locally running geth node and asks the user to confirm a deposit from his/her personal account.

-

Validator Client Connects & Listens to Incoming Headers from the Geth Node and Assigns User as Validator on a Shard per Period: the validator is selected for the current period and must accept collations from proposer nodes that offer the best prices.

-

Concurrently, the Proposer Client Processes and Executes Pending tx’s from the Geth Node: the proposer client will create valid collations and submit them to validators on an open bidding system.

-

Validators Will Select Collation Proposals that Offer Highest Payout: Validators listen to collation headers on a certain shard with high deposit sizes and sign them.

-

The Validator Adds Collation Headers Through the VMC: the validator client calls the add_header function in the VMC and to do on-chain verification of the countersigned and accepted collation header immediately.

-

The User Will be Selected as Validator Again on the VMC in a Different Period or Can Withdraw His/Her Stake from the Validator Pool: the user can keep staking and adding incoming collation headers and restart the process, or withdraw his/her stake and be removed from the VMC validator set.

Now, we’ll explore our architecture and implementation in detail as part of the go-ethereum repository.

System Start and User Entrypoint

Our Ruby Release will require users to start a local geth node running a localized, private blockchain to deploy the VMC into. Then, users can spin up a validator client as a command line entrypoint into geth while the node is running as follows:

$ geth sharding-validator --deposit --datadir /path/to/your/datadir --password /path/to/your/password.txt --networkid 12345

If it is the first time the client runs, it will deploy a new VMC into the local chain and establish a JSON-RPC connection to interact with the node directly. The --deposit flag tells the sharding client to automatically unlock the user’s keystore and begin depositing ETH into the VMC to become a validator.

If the initial deposit is successful, the sharding client will launch a local, transaction simulation generator, which will queue transactions into the txpool for the geth node to process that can then be added into collations on a shard.

Concurrently, a user will need to launch a proposer client that will start processing transactions into collations that can then be “sold” to validators by including a cryptographic proof of an eth deposit in their unsign collation headers. This proof is a guarantee of a state change in the validator’s account balance for accepting to sign the incoming collation header. The proposer client (also known as a collator) can also be initialized as follows in a separate process:

geth sharding-collator --datadir /path/to/your/datadir --password /path/to/your/password.txt --networkid 12345

Back to the validators, the validator client will begin its main loop, which involves the following steps:

-

Subscribe to Incoming Block Headers: the client will begin by issuing a subscription over JSON-RPC for block headers from the running geth node.

-

Check Shards for Eligible Proposer: On incoming headers, the client will interact with the VMC to check if the current validator is an eligible validator for an upcoming periods (only a few minutes notice)

-

If Validator is Selected, Fetch Proposals from Proposal Nodes and Add Collation Headers to VMC: Once a validator is selected, he/she only has a small timeframe to add collation headers through the VMC, so he/she looks for proposals from proposer nodes and accepts those that offer the highest payouts. The validator then countersigns the collation header, receives the full collation with its body after signing, and adds it to the VMC through PoS consensus.

-

Supernode Reconciles and Adds to Main Chain: Supernodes that will be responsible for reconciling global state across shards into the main Ethereum blockchain. They are tasked with observing the state across the whole galaxy of shards and adding blocks to the canonical PoW main chain. Proposers get rewarded to their coinbase address for inclusion of a block (also known as a collation subsidy).

-

If User Withdraws, Remove from Validator Set: A user can choose to stop being a validator and then his/her ETH is withdrawn from the validator set.

-

Otherwise, Validating Client Keeps Subscribing to Block Headers: If the user chooses to keep going,

It will be the proposer client’s responsibility to listen to any new broadcasted transactions to the node and interact with validators that have staked their ETH into the VMC through an open bidding system for collation proposals. Proposer clients are the ones responsible for state execution of transactions in the tx pool.

The Validator Manager Contract

Our solidity implementation of the Validator Manager Contract follows the reference spec outlined by Vitalik here.

Necessary functionality

In our Solidity implementation, we begin with the following sensible defaults:

// Constant values

uint constant periodLength = 5;

int constant public shardCount = 100;

// The exact deposit size which you have to deposit to become a validator

uint constant depositSize = 100 ether;

// Number of periods ahead of current period, which the contract

// is able to return the collator of that period

uint constant lookAheadPeriods = 4;

Then, the 4 minimal functions required by the VMC are as follows:

Depositing ETH and Becoming a Validator

function deposit() public payable returns(int) {

require(!isValidatorDeposited[msg.sender]);

require(msg.value == depositSize);

...

}

deposit adds a validator to the validator set, with the validator's size being the msg.value (i.e., the amount of ETH deposited) in the function call. This function returns the validator index.

Determining an Eligible Proposer for a Period on a Shard

function getEligibleProposer(int _shardId, int _period) public view returns(address) {

require(_period >= lookAheadPeriod);

require((_period - lookAheadPeriods) * periodLength < block.number);

...

}

The getEligibleProposer function uses a block hash as a seed to pseudorandomly select a signer from the validator set. The chance of being selected should be proportional to the validator's deposit. The function should be able to return a value for the current period or any future up to LOOKAHEAD_PERIODS periods ahead.

Withdrawing From the Validator Set

function withdraw(int _validatorIndex) public {

require(msg.sender == validators[_validatorIndex].addr);

...

}

Authenticates the validator and it removes him/her from the validator set and refunds the deposited ETH.

Processing and Verifying a Collation Header

function addHeader(int _shardId, uint _expectedPeriodNumber, bytes32 _periodStartPrevHash,

bytes32 _parentHash, bytes32 _transactionRoot,

address _coinbase, bytes32 _stateRoot, bytes32 _receiptRoot,

int _number) public returns(bool) {

HeaderVars memory headerVars;

// Check if the header is valid

require((_shardId >= 0) && (_shardId < shardCount));

require(block.number >= periodLength);

require(_expectedPeriodNumber == block.number / periodLength);

require(_periodStartPrevHash == block.blockhash(_expectedPeriodNumber * periodLength - 1));

…

}

The addHeader function is the most importance in the VMC as it is what provides on-chain verification of collation headers immediately and maintains a canonical ordering of processed collation headers by firing a CollationAdded event log.

Our current solidity implementation includes all of these functions along with other utilities important for the our Ruby Release sharding scheme.

Validator Sampling

The probability of being selected as a validator on a particular shard should be completely dependent on the stake of the validator and not on other factors. This is a key distinction. As specified in the Sharding FAQ by Vitalik, “if validators could choose, then attackers with small total stake could concentrate their stake onto one shard and attack it, thereby eliminating the system’s security.”

The idea is that validators should not be able to figure out which shard they will become a validator of and during which period they will be assigned with anything more than a few minutes notice. To accomplish this, random sampling would require validators to redownload entire large parts of new shard states they get assigned to as part of the collation process in a naive approach. However, our approach separates the consensus and state execution/collation proposal mechanisms, which allows validators to not have to download shard states save for specific situations.

Ideally, we want validators to shuffle across shards very rapidly and through a trustworthy source of randomness built in-protocol.

Although this separation of consensus and state execution is an attractive way to fix the overhead of having to redownload shard states, random sampling does not help in a bribing, coordinated attack model. In Vitalik’s own words:

"Either the attacker can bribe the great majority of the sample to do as the attacker pleases, or the attacker controls a majority of the sample directly and can direct the sample to perform arbitrary actions at low cost (O(c) cost, to be precise). At that point, the attacker has the ability to conduct 51% attacks against that sample. The threat is further magnified because there is a risk of cross-shard contagion: if the attacker corrupts the state of a shard, the attacker can then start to send unlimited quantities of funds out to other shards and perform other cross-shard mischief. All in all, security in the bribing attacker or coordinated choice model is not much better than that of simply creating O(c) altcoins.”

However, this problem transcends the sharding scheme itself and goes into the broader problem of fraud detection, which we have yet to comprehensively address.

Collation Header Approval

Explains the on-chain verification of a collation header.

Work in progress.

Event Logs

Explain how CollationAdded logs will later on be used.

Work in progress.

The Validator Client

The main running thread of our implementation is the validator client, which serves as a bridge between users staking their ETH, proposers offering collations to these validators, and the Validator Manager Contract that verifies collation headers on-chain.

When we launch the client with

geth sharding-validator --deposit --datadir /path/to/your/datadir --password /path/to/your/password.txt --networkid 12345

The instance connects to a running geth node via JSON-RPC and calls the deposit function on a deployed, Validator Manager Contract to insert the user into a validator set. Then, we subscribe for updates on incoming block headers and call getEligibleProposer on receiving each header. Once we are selected, our client fetches and “purchases” proposed, unsigned collations from a proposals pool created by proposer nodes. The validator client accepts a collation that offer the highest payout, countersigns it, and adds it to the VMC all within that period.

Local Shard Storage

Local shard information will be done through the same LevelDB, key-value store used to store the mainchain information in the local data directory specified by the running geth node. Adding a collation to a shard will effectively modify this key-value store.

Work in progress.

The Proposer Client

In addition to launching a validator client, our system will require a user to concurrently launch a proposer client that is tasked with state execution, fetching pending tx’s from the running geth node’s txpool, and creating collations that can be sent to validators.

Users will launch a proposal client as another geth entrypoint as follows:

geth sharding-collator --datadir /path/to/your/datadir --password /path/to/your/password.txt --networkid 12345

Launching this command will connect via JSON-RPC to fetch the geth node’s tx pool and see who the currently active validator node is for the period. The proposer is tasked with running transactions to create valid collations and executing their required computations, tracking used gas, and all the heavy lifting that is usually seen in full Ethereum nodes. Once a valid collation is created, the proposer broadcasts the unsigned header (note: the body is not broadcasted) to a proposals pool along with a guaranteed ETH deposit that is extracted from the proposer’s account upfront. Then, the current validator assigned for the period will find proposals for her/her assigned shard and sign the one with the highest payout.

Then, the validator node will call the addHeader function on the VMC by submitting this collation header. We’ll explore the structure of collation headers in this next section along with important considerations for state execution, as this can quickly become the bottleneck of the entire sharding system.

Collation Headers and State Execution

Work in progress.

Peer Discovery and Shard Wire Protocol

Work in progress.

Protocol Modifications

Protocol Primitives: Collations, Blocks, Transactions, Accounts

(Outline the interfaces for each of these constructs, mention crucial changes in types or receiver methods in Go for each, mention transaction access lists)

Work in progress.

The EVM: What You Need to Know

As an important aside, we’ll take a brief detour into the EVM and what we need to understand before we modify it for a sharded blockchain. At its core, the functionality of the EVM optimizes for security and not for computational power with the following restrictions:

- Every single step must be paid for upfront with gas costs to prevent DDoS

- Programs can't interact with each other without a single byte array

- This also means programs can't access other programs' state

- Sandboxed Execution - the EVM can only modify its internal state and nothing else

- Deterministic execution guarantees

So what exactly is the EVM? The EVM was purposely designed to be a stack based machine with memory-byte arrays and key-value stores that are kept on merkle trees

- Every single keys and storage values are 32 byte

- There are 100 total opcodes in the EVM

- The EVM comes with a temporary memory byte-array and storage tree to hold persistent memory.

The only crypto operation in the EVM is the sha3 hash function. Aside from that, the EVM provides a bunch of blockchain access-level context that allows certain opcodes to fetch useful information from the external system. For example, LOG opcodes store useful information in the log bloom filter that can be synced with light clients

Additionally, the EVM contains a call-depth limit such that recursive invocations or chains of calls will eventually halt, preventing a drastic use of resources.

It is important to note that the merkle root of an Ethereum account is updated any time an SSTORE opcode is executed successfully by a program on the EVM that results in a key or value changing in the state merklix (merkle radix) tree.

How is this relevant to sharding? It is important to note the importance of certain opcodes in our implementation and how we will need to introduce and modify several of them for both security and scalability considerations in a sharded chain.

Work in progress.

Sharding In-Practice

Fork Choice Rule

In the sharding consensus mechanism, it is important to consider that we now have two layers of longest chain rules when adding a collation. When we are reaching consensus on the best shard chain, we not only have to check for the longest canonical main chain, but also the longest shard chain within this longest main chain. Vlad Zamfir has elaborated on this fork-choice rule in a tweet that is important for our sharding scheme.

Use-Case Stories: Proposers

The primary purpose of proposers is to use their computational power for state execution of transactions and create valid collations that can then be put on an open market for validators to take. Upon offering a proposal, proposers will deposit part of their ETH as a payout to the validator that adds its collation header to the VMC, even if the collation gets orphaned. By forcing proposers to take on this risk, we prevent a certain degree of collation proposal spamming, albeit not without a few other security problems: (See: Active Research).

The primary incentive for proposers to generate these collations is to receive a payout to their coinbase address along with transactions fees from the ones they process once added to a block in a canonical chain.

Use-Case Stories: Validators

The primary purpose of validators is to use Proof of Stake and reach consensus on valid shard chains based on the collations they process and add to the Validator Manager Contract. They have two primary options they can choose to do:

- They can deposit ETH into the VMC and become a validator. They then have to wait to be selected by the VMC on a particular period to add a collation header to the VMC.

- They can accept the collation proposals with the highest payouts from the collation pool during their eligible period.

- They can withdraw their stake and stop being a part of the validator pool

The primary incentive for validators is to earn the payouts from the proposers offering them collations within their period.

Current Status

Currently, Prysmatic Labs is focusing its initial implementation around the logic of the validator and proposer clients. We have built the command line entrypoints as well as the minimum, required functions of the Validator Manager Contract that is deployed to a local Ethereum blockchain instance. Our validator client is able to subscribe for block headers from the running Geth node and determine when we are selected as an eligible proposer in a given period if we have deposited ETH into the contract.

You can track our progress, open issues, and projects in our repository here.

Security Considerations

Not Included in Ruby Release

Under the uncoordinated majority model, in order to prevent a single shard takeover, random sampling is utilized. Each shard is assigned a certain number of Collators and the collators that approve the collations on that shard are sampled randomly. However for the ruby release we will not be implementing any random sampling of the collators of the shard as the primary objective of this release is to launch an archival sharding client which deploys the Validator Management Contract to a locally running geth node.

Also for now we will not be implementing challenge response mechanisms to mitigate instances where malicious actors are penalized and have their staked slashed for making incorrect claims regarding the veracity of collations

We will not be considering data availability proofs as part of the ruby release we will not be implementing them as it just yet as they are an area of active research.

Bribing, Coordinated Attack Models

Work in progress.

Enforced Windback

When collators are extending collator chains by adding headers to the VMC, it is critical that they are able to verify some of the collation headers in the immediate past for security purposes. There have already been instances where mining blindly has led to invalid transactions that forced Bitcoin to undergo a fork (See: BIP66 Incident).

As part of the sharding process, we want to ensure validators do two things when they look at the immediate past:

Validity of collations through checking the integrity of transactions within their body. Checking for availability of the data within past collation bodies.

This checking process is known as “windback”. In a post by Justin Drake on ETHResearch, he outlines that this is necessary for security, but is counterintuitive to the end-goal of scalability as this obviously imposes more computational and network constraints on validator nodes.

One way to enforce validity during the windback process is for validators to produce zero-knowedge proofs of validity that can then be stored in collation headers for quick verification.

On the other hand, to enforce availability for the windback process, a possible approach is for validators to produce “proofs of custody” in collation headers that prove the validator was in possession of the full data of a collation when produced. Drake proposes a constant time, non-interactive zkSNARK method for validators to check these proofs of custody. In his construction, he mentions splitting up a collation body into “chunks” that are then mixed with the validators private key through a hashing scheme. The security in this relies in the idea that a validator would not leak his/her private key without compromising him or herself, so it provides a succinct way of checking if the full data was available when a validator processed the collation body and proof was created.

Explicit Finality for Stateless Clients

Vitalik has mentioned that the average amount of windback, or how many immediate periods in the past a validator has to check before adding a collation header, is around 25. In a medium post on the value of explicit finality for sharding, Hsiao-Wei Wang mentions how the finality that Casper FFG provides would mean stateless clients would be entirely confident of blocks ahead to prevent complete reshuffling and faster collation processing. In her own words:

“Casper FFG will provide explicit finality threshold after about 2.5 “epoch times”, i.e., 125 block times [1][7]. If validators can verify more than 125 / PERIOD_LENGTH = 25 collations during reshuffling, the shard system can benefit from explicit finality and be more confident of the 25 ahead collations from now are all finalized.”

Casper allows us to forego some of these windback considerations and reduces the number of constraints on scalability from a collation header verification standpoint.

The Data Availability Problem

Introduction and Background

Work in progress.

On Uniquely Attributable Faults

Work in progress.

Erasure Codes

Work in progress.

Beyond Phase 1

Cross-Shard Communication

Receipts Method

Work in progress.

Merge Blocks

Work in progress.

Synchronous State Execution

Work in progress.

Transparent Sharding

One of the first question dApp developers ask about sharding is how much will they need to change their workflow and smart contract development to adopt the sharded blockchain scheme. An idea tangentially explored by Vitalik in his Sharding FAQ was the concept of “transparent sharding” which means that sharding will exist exclusively at the protocol layer and will not be exposed to developers. The Ethereum state system will continue to look as it currently does, but the the protocol will have a built-in system that creates shards, balances state across shards, gets rid of shards that are too small, and more. This will all be done behind the scenes, allowing devs to continue their current workflow on Ethereum. This was only briefly mentioned, but will be critical to ensure a better user experience moving forward after security considerations are addressed.

Tightly-Coupled Sharding (Fork-Free Sharding)

A current problem with the scheme we are following for sharding is the reliance on two fork-choice rules. When we are reaching consensus on the best shard chain, we not only have to check for the longest canonical, main chain, but also the longest shard chain within this longest main chain. Fork-choice rules have long been an approach to solve the constraints that distributed systems impose on us due to factors outside of our control (Byzantine faults) and are the current standard in most public blockchains.

A problem that can occur with current distributed fork-choice ledgers is the possibility of choosing a wrong fork and continuing to do PoW on it, thereby wasting potential profits of mining on the canonical chain. Another current burden is the large amount of data that needs to be downloaded in order to validate which fork is potentially the best one to follow in any situation, opening up avenues for spam DDoS attacks.

Fortunately, there is a potential method of creating a fork-free sharding mechanism that relies on what we are currently implementing through the Validator Manager Contract that has been explored by Justin Drake and Vitalik in this and this other post, respectively.

The current spec of the Validator Manager Contract already does a canonical ordering of collation headers for us (i.e. we can track the timestamped logs of collation headers being added). Because the data for the VMC lives on the canonical main chain, we are able to easily extract and exact ordering and validity from headers added through the contract.

To add validity to our current VMC spec, Drake mentions that we can use a succinct zkSNARK in the collation root proving validity upon construction that can be checked directly by the addHeader function on the the VMC.

The other missing piece is the guarantee of data availability within collation headers submitted to the VMC which can once again be done through zero-knowledge proofs and erasure codes (See: The Data Availability Problem). By escalating this up to the VMC, we can ensure what Vitalik calls “tightly-coupled” sharding, in which case breaking a single shard would entail also breaking the progression of the canonical chain, enabling easier cross-shard communication due to having a single source of truth being the VMC and the associated collation headers it has processed. In Justin Drake’s words, “there is no fork-choice rule within the VMC”.

It is important to note that this “tightly coupled” sharding has been relegated to Phase 4 of the roadmap.

Work in progress.

Active Questions and Research

Separation of Proposals and Consensus

In a recent blog post, Vitalik has outlined a novel system to the sharding mechanism through better separation of concerns. In the current reference documentation for a sharding systems, validators are responsible for proposing transactions into collations and reaching consensus on these proposals. That is, this process happens all at once, as proposing a collation happens in tandem with consensus.

This leads to significant computational burdens on validators that need to keep track of the state of a particular shard in the proposal process as part of the transaction packaging process. The potentially better approach outlined above is the idea of separating the transaction packaging process and the consensus mechanism into two separate nodes with different responsibilities. Our model will be based on this separation and we will be releasing a proposer client alongside a validator client in our Ruby release.

The two nodes would interact through a cryptoeconomic incentive system where proposers would package transactions and send unsigned collation headers (with obfuscated collation bodies) over to validators with a signed message including a deposit. If a validator chooses to accept the proposal, he/she would be rewarded by the amount specified in the deposit. This would allow proposers to focus all of their computational power solely on state execution and organizing transactions into proposals.

Along the same lines, it will make it easier for validators to constantly jump across shards to validate collations, as they no longer have the need for resyncing an entire state tree because they can simply receive collation proposals from proposer nodes. This is very important, as validator reshuffling is a crucial security consideration to prevent shard hostile takeovers.

A key question asked in the post is whether “this makes it easy for a proposer to censor a transaction by paying a high pass-through fee for collations without a certain transaction?” and the answer to that is that yes, this could happen but in the current system a proposer could censor transactions by simply not including them (see: The Data Availability Problem).

It is important to note a possible attack vector in this case: which is that a an attacker could spam proposals on a particular shard and take on the price of excluding certain transactions as a censorship mechanism while the validators would have no idea this is happening. However, given a competitive enough proposal economy, this would be very similar to the current problem of transaction spam in traditional blockchains.

In this system, validators would get paid the proposal’s deposit even if the collation does not get appended to the shard. Proposers would have to take on this risk to mitigate the possibilities of malicious intent to make an obfuscated-collation-body proposal system work. Only collations that are double signed and have an available body can be included in the main chain, fee F goes to the validator regardless whether collation gets into the main chain, but fee T only goes to the proposer if the collation gets included to the main chain.

In practice, we would end up with a system of 3 types of nodes to ensure the functioning of a sharded blockchain

- Proposer nodes that are tasked with state execution and creation of unsigned collation headers, obfuscated collation bodies, data availability proofs, and an ETH deposit to be relayed to validators.

- Validator nodes that accept proposals through an open auction system similar to way transactions fees currently work. These nodes then sign these collations and pass them through the VMC for inclusion into a shard through PoS.

Selecting Eligible Validators Off-Chain

In our current implementation for the Ruby Release, we are selecting validators on-chain by calling the getEligibleProposer function from the VMC directly. Justin Drake proposes an alternative scheme that could potentially open up new validator selection mechanisms off-chain through a fork-choice rule in this post on ETHResearch.

In his own words, this scheme “saves gas when calling addHeader and unlocks the possibility for fancier proposer eligibility functions”. A potential way to do so would be through private validator sampling which is elaborated on below:

“We now look at the problem of private sampling. That is, can we find a proposal mechanism which selects a single validator per period and provides “private lookahead”, i.e. it does not reveal to others which validators will be selected next? There are various possible private sampling strategies (based on MPCs, SNARKs/STARKs, cryptoeconomic signalling, or fancy crypto) but finding a workable scheme is hard. Below we present our best attempt based on one-time ring signatures. The scheme has several nice properties: Perfect privacy: private lookahead and private lookbehind (i.e. the scheme never matches eligible proposers with specific validators) Full lookahead: the lookahead extends to the end of the epoch (epochs are defined below, and have roughly the same size as the validator set) Perfect fairness: within an epoch validators are selected proportionally according to deposit size, with zero variance” - Justin Drake

Community Updates and Contributions

Excited by our work and want to get involved in building out our sharding releases? We created this document as a single source of reference for all things related to sharding Ethereum, and we need as much help as we can get!

You can explore our Current Projects in-the works for the Ruby release. Each of the project boards contain a full collection of open and closed issues relevant to the different parts of our first implementation that we use to track our open source progress. Feel free to fork our repo and start creating PR’s after assigning yourself to an issue of interest. We are always chatting on Gitter, so drop us a line there if you want to get more involved or have any questions on our implementation!

Contribution Steps

- Create a folder in your

$GOPATHand navigate to itmkdir -p $GOPATH/src/github.com/ethereum && cd $GOPATH/src/github.com/ethereum - Clone our repository as

go-ethereum,git clone https://github.com/prysmaticlabs/geth-sharding ./go-ethereum - Fork the

go-ethereumrepository on Github: https://github.com/ethereum/go-ethereum - Add a remote to your fork `git remote add YOURNAME https://github.com/YOURNAME/go-ethereum

Now you should have a remote pointing to the origin repo (geth-sharding) and to your forked, go-ethereum repo on Github. To commit changes and start a Pull Request, our workflow is as follows:

- Create a new branch with a clear feature name such as

git checkout -b collations-pool - Issue changes with clear commit messages

- Push to your remote

git push YOURNAME collations-pool - Go to the geth-sharding repository on Github and start a PR comparing

geth-sharding:masterwithgo-ethereum:collations-pool(your fork on your profile). - Add a clear PR title along with a description of what this PR encompasses, when it can be closed, and what you are currently working on. Github markdown checklists work great for this.

Acknowledgements

A special thanks for entire Prysmatic Labs team for helping put this together and to Ethereum Research (Hsiao-Wei Wang) for the help and guidance in our approach.

References

Ethereum Sharding and Finality - Hsiao-Wei Wang

Data Availability and Erasure Coding

Proof of Visibility for Data Availability

Enforcing Windback and Proof of Custody

State Execution Scalability and Cost Under DDoS Attacks

Guaranteed Collation Subsidies

Fork Choice Rule for Collation Proposals

Model for Phase 4 Tightly-Coupled Sharding

History, State, and Asynchronous Accumulators in the Stateless Model